On the cusp of a major political shift in the US, it feels like an appropriate time to talk about risk. The draft revision 3 of the Good Clinical Practice guideline uses the word “risk” 74 times – more than double the 36 mentions in R2. We’re meant to take risk-based approaches to protocol design, participant safety, data integrity, site monitoring, computer system validation, data capture system design, sponsor oversight, audits, blinding, data cleaning, and “critical-to-quality” factors (whatever they are; more on that in a future post).

Accordingly, we’re going to look outside our industry for best practices in risk management with a Risk Management Book Club. This week’s book is the provocatively-titled The Failure of Risk Management: Why It’s Broken and How to Fix It, by Douglas W. Hubbard (Wiley, 2020). Hubbard is the founder of Hubbard Decision Research, a consulting firm that uses quantitative methods to help organizations make better decisions.

Hubbard describes the gold standard of risk management as a set of quantitative, validated models used to run simulations that help an organization evaluate both risk and the likely return on mitigation methods. The middle-of-the-road method for risk management is “expert intuition” – a bunch of executives sitting around making guesses about what they think will go wrong, without any formal methodology. The worst method, he argues, is the pseudo-quantitative method – the “scorecard” for assessing risks on the three axes of impact, detectability, and likelihood, resulting in a number that is used to drive risk mitigation decisions.

If that last method sounds familiar, it should: it’s the risk management process outlined in E6 R2 and R3, and it’s been used for years in clinical trials for all kinds of risk evaluations, from risk-based vendor qualification to risk-based monitoring and beyond.

Per Hubbard, the pseudo-quantitative method is “worse than useless” – he cites research to show it introduces errors into the decision-making process that would not be made using the “expert intuition” method:

“Doing nothing is not as bad as things can get for risk management. The worst thing to do is to adopt an unproven method—whether or not it seems sophisticated—and act on it with high confidence.”Clinical trial researchers of the world, unite! You have nothing to lose but your RACT!

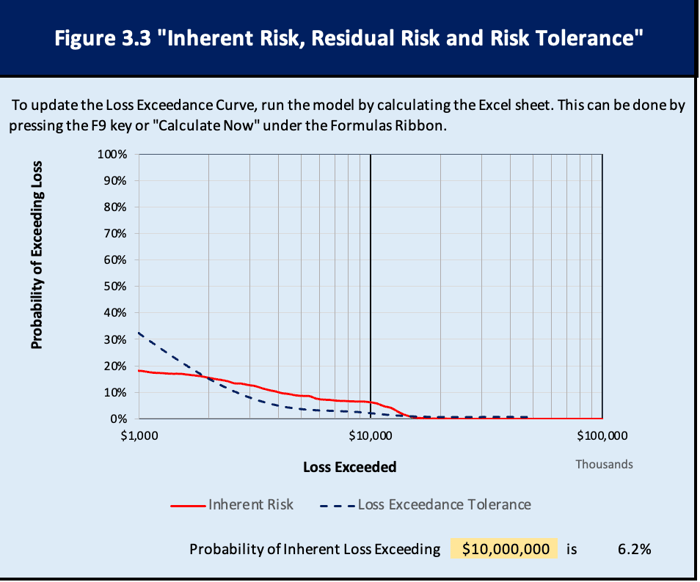

Where does clinical trial risk management go from here? Admittedly, it’s difficult to produce a sophisticated, validated quantitative risk management model for a single clinical trial. Maybe it’s time to jettison scorecards and embrace “vibes” as a valid method of managing risk. Hubbard presents a Monte Carlo spreadsheet that can be used in lieu of the RACT or scorecard to help us assess the probability of particular events and quantify the monetary value of their impact. The spreadsheet then runs one thousand simulations and generates a “Loss Exceedence Curve,” which “adds up” the risks and shows you the probability of losing various amounts of money over the time period of the assessment. You can then enter the cost of mitigation for each risk and the likelihood of effectiveness to determine whether a particular risk mitigation step is worth it.

This method, Hubbard notes, is not a true validated quantitative model, but it does lend more rigor to expert intuition. He describes exercises that teams can use to “calibrate” subjective probability estimates and confidence intervals so this method is less prone to error. The spreadsheet is available here .

A clinical study team would have to shift its mindset quite a bit to use this risk mitigation method. We tend not to think of risk in monetary terms – but perhaps we should?

The Failure of Risk Management is clearly written and shows us how professional risk managers think about risk. Hubbard’s How to Measure Anything: Finding the Value of “Intangibles” in Business is another terrific resource that will change how you think about metrics.