(Word count: 512)

Most inspection teams employ storyboards in advance of an inspection, but there is no industry consensus on their content or use. The concept originated in filmmaking, where it referred to cartoon-like representations of the shot sequence for a scene. In movies, storyboards are planning tools, but in inspections, we use them post-hoc, to provide a narrative arc to a messy series of events.

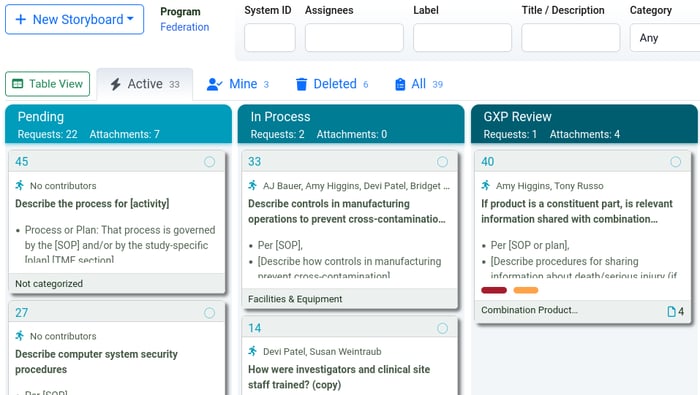

Through trial and error, we find that storyboards work best when they are limited to high-level talking points about an issue, a few bullet points that can fit easily on a slide, to be memorized by an interviewee as a first-line response to a question. The storyboards should include references to documents in the Trial Master File (TMF) that give the fine details, but there is no point on duplicating this level of detail; the storyboard cannot anticipate the direction of the interview after the initial question, and the interviewee should reference source documents from the TMF when providing details to the inspector. Compiling an extensive "dossier" to answer an inspection question is not a good use of time; much better to focus on filing and organizing the TMF to ensure the details can be located easily there.

Although storyboards are high level, they should tell a complete quality story for every issue. The beginning of a quality story is always the SOP, plan, or specification that serves as the requirement for the activity. The middle of the quality story explains that work was done per the activity. The end of the quality story tells where the activities were documented.

Many teams focus their storyboards on explaining deviations and don't spend enough time preparing interviewees to talk about regular processes. It's surprisingly difficult to describe processes that are part of the standard fabric of clinical research, such as informed consent or financial disclosure, without preparation. FDA's Bioresearch Monitoring Compliance Program Manual for sponsors is a good starting point for expected questions. EMA's Annex IV to its inspection procedure is a bit less detailed but also worth consulting. Standard "process" storyboards help interviewees feel confident about answering basic questions, which will help them deal with the "gotcha" questions.

Storyboards about deviations also need to tell a quality story, starting with the requirement and proceeding to the deviation. The compelling part of the story, though, is what the team did in response: Correction, root cause analysis, corrective and preventative action, and effectiveness check should all be described in bullet points, with a short impact analysis. Inspectors are less likely to issue a finding for an issue that has been properly handled.

If during inspection prep the team finds that little has been done to address a significant issue, it's not too late to issue a CAPA--better late than never. If there is no useful GCP CAPA SOP in place, it's not too late for that either. The storyboard should not be the only documentation of the CAPA.

To summarize:

- Less is more

- Tell a quality story

- Prepare for both expected and "problem" questions

- Better late than never for addressing deviations

Photo by Matt Popovich on Unsplash